Imagine a world without GPS on your phone. One without the internet to look up directions. Long before the days of satellites or even printed atlases. Where people not only didn’t know about the entire world, it hadn’t even been discovered. There were places humanity hadn’t found yet (I guess space is like that nowadays).

It was during such a time, in 1739, that Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier was on an exploration mission in the South Atlantic and sighted an island, though he did not make landfall. He even mislabeled the coordinates, making it difficult for anyone else to find the island. While sailing roughly the same area in 1772 James Cook couldn’t spot it and so assumed it didn’t exist.

In fact, it wasn’t sighted again until 1808, when British whaler James Lindsay encountered it and named it after himself, like all explorers seem to do, even though he also didn't land on the island. Then in 1822 an American sailor named Benjamin Morrell claimed to have set foot on it, though many historians disputed this claim. A few years later, in 1825, the island was claimed for the British Crown by George Norris, who renamed it Liverpool Island.

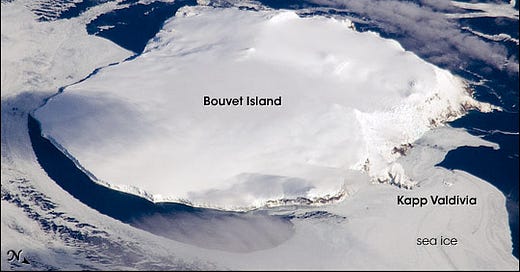

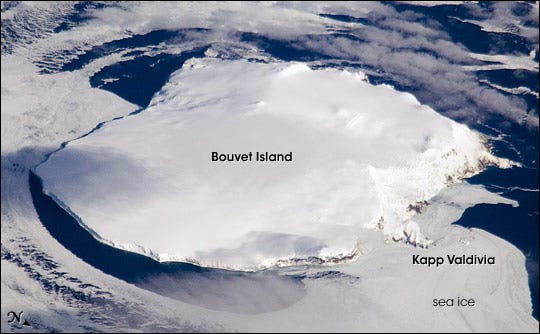

A hundred years later, in 1927, a Norwegian expedition landed on the island for an extended time, the first mission of its kind, and claimed it for Norway. It was only then that it was given its current name, Bouvet Island. After years of territorial disputes between Norway and Britain, since it had been so hard to find and been mislabeled in the first place, Bouvet was finally declared a Norwegian dependency in 1930. In 1971, it was designated a nature reserve. It wasn’t until March 1985 that a Norwegian expedition experienced sufficiently clear weather to allow the entire island to be photographed from the air, resulting in the first accurate map of the whole island, nearly 250 years after its discovery.

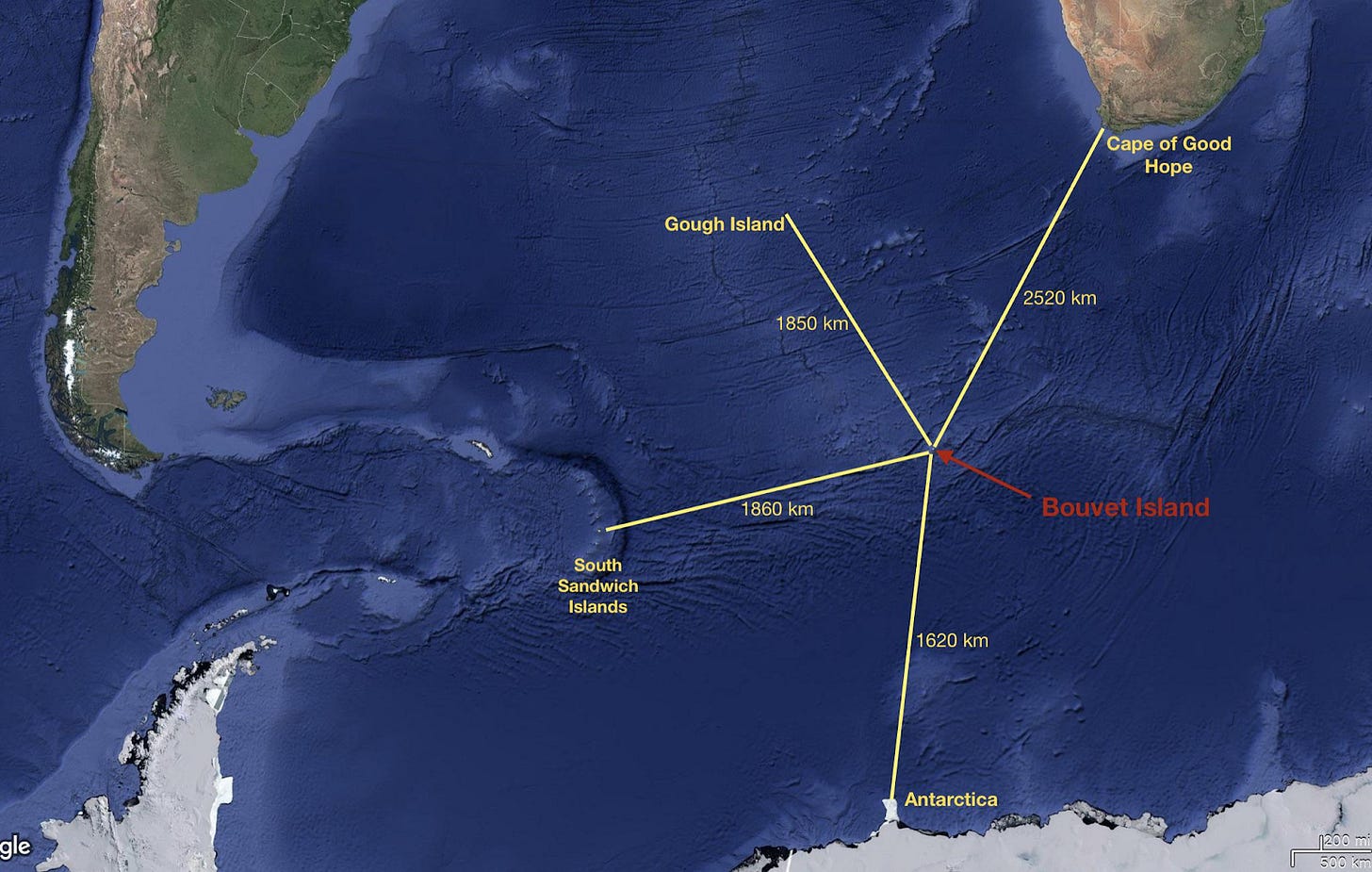

Bouvet Island lies approximately midway between the furthest tip of southern Africa and Antarctica, which is over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to the south. It is on the junction of three tectonic plates, so is mostly formed from a volcano and is almost entirely covered by glaciers.

Nowadays the island hosts an automatic meteorological station and a research station on the north-western part of the island, which can accommodate six people for periods of 2–4 months.

Now that humanity knows what it is and how to find it, go Google Maps it.