“Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you.”

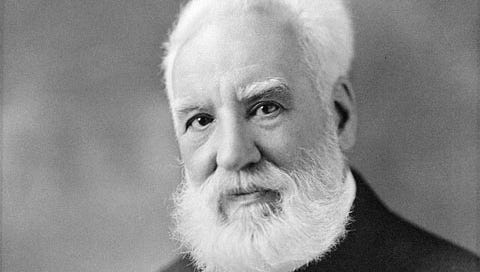

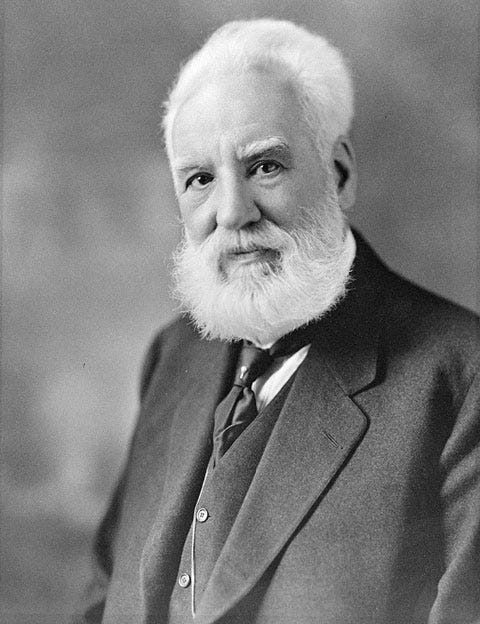

No, it wasn’t Sherlock Holmes asking for his trusty colleague, or Francis Crick requesting his famous co-author. It was, instead, Scottish-born, Canadian/American inventor Alexander Graham Bell. He was calling to his assistant, Thomas Watson from a completely separate room in a building via the newfangled device Bell had created, the telephone. Those words marked the first successful test of the phone on this date, 10 March 1876. Though who receives credit as “inventor” of the telephone is shrouded in controversy.

The idea of two devices connected by a string or wire to transmit sound has been around for hundreds of years. Just look at kids using metal cans connected to a string to realize the concept itself is easy to understand. The trick, of course, is making the sounds discernable over long distances. The electromagnetic telegraph was invented in the 1830s, which laid the groundwork for the later telephone. By the late 18th century engineers had managed to improve upon the electromagnetic signals of the telegraph to turn them into audible sounds.

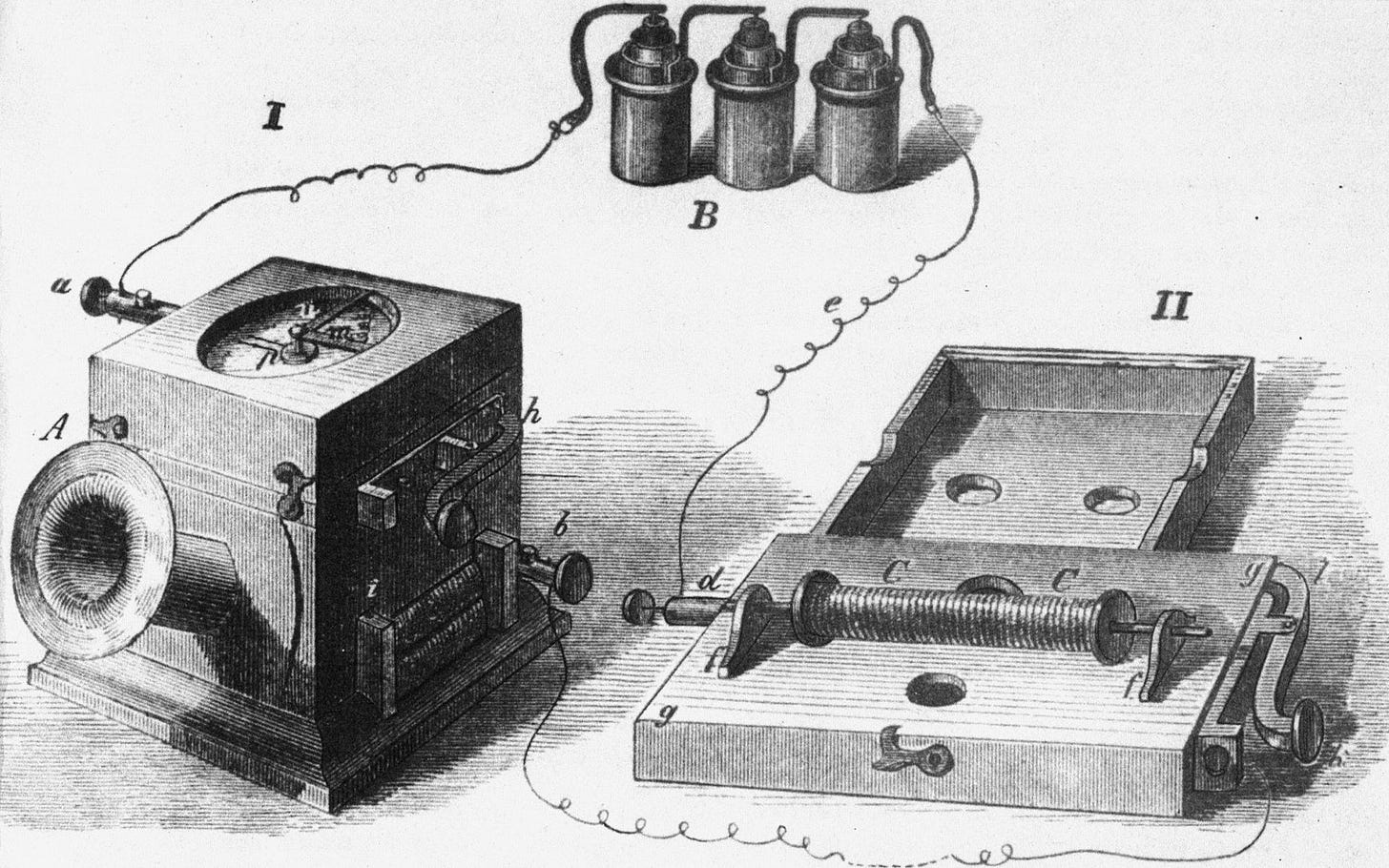

In 1861, German scientist Johann Philipp Reis created a device in Germany that captured sound, converted it into electrical impulses, then transmitted it via electrical wires to another device, and transformed them into recognizable sounds. He coined the word “telephone” to describe the device, which he intended to transmit music. While his telephone was able to transmit conversation, the microphone was weak and complex, making the whole device impractical.

A decade later Italian inventor Antonio Meucci filed a patent caveat – basically a hold on a patent that doesn’t include a working model – for a proto-telephone in New York in 1871. If he had been able to afford the renewing license of the caveat, then no other inventors could have filed a patent for a similar device while his was still in effect. He let it lapse in 1874, however, freeing others to file their own patents.

The real controversy, however, arose between Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray. Both inventors actually filed their patent applications on the same day, 14 February 1876 (yes, before the famous call demonstrating the phone’s practicality), both used a similar transmission device, and there was a similarity between the drawings submitted as part of the application. There remains debate about who arrived at the patent office first (well, whose lawyer, on their behalf), which would give them an official claim to the patent. Some stories suggest that Gray’s representatives arrived early in the morning, possibly even before the office opened, to submit, but did not pay the fee immediately and so went to the bottom of the pile. Some claim that Bell’s lawyer arrived first, giving him the rightful claim; while others suggest that Bell’s lawyer paid the fee (and possibly a bribe as well) to jump the line and speed the process in favor of his client.

There was also a section in Bell’s patent application that described a specific feature necessary for the telephone function. That feature was not included as part of Bell’s drawings, but was part of Gray’s drawings. Exactly when that feature was inserted (which itself has never been in doubt) and by whom remains controversial. Whatever the actual truth, Bell was eventually awarded the patent and has since become the “inventor” of the telephone.

Within two years the first telephone line, the first switchboard, and the first telephone exchange were created and in operation. In 1880 Bell formed the American Bell Telephone Company to run the exchanges and then co-found the American Telegraph and Telephone Company (AT&T) in 1885. By the end of the century there were almost 600,000 phones in use, which shot up to more than 2 million by 1905, and nearly tripled to close to 6 million by 1910. Bell’s companies had an almost complete monopoly on phone and telegraph services in the US, making Bell an exceptionally wealthy man.

Today, AT&T is just one of many telecommunication companies (which notoriously drops phone calls, according to comedian John Oliver) and phone’s fit into pockets without needing a metal line to connect them to others. So, Mr. Watson, can you hear me now?