Boasting a collection of more than 7 million objects from around the world (more on that later), the British Museum, as of 2021, was the third most-visited museum in the world with over 4 million annual visitors. It had received a record 6.7 million visitors in 2013, but global pandemics and economic depressions in the intervening years tend to put a damper on travel and going out.

It’s no wonder that visitors flock to the museum. Its collection includes well-known artifacts of history such as the “Elgin” or Parthenon Marbles, more than 700 bronze pieces known as the Benin Bronzes, and the Rosetta Stone. People keep returning due to the sheer scale and size, covering almost 1 million square feet in an entire block in the Bloomsbury district of London. Even before acquiring those objects it attracted famous visitors. When still a child, Mozart and his family visited the Museum towards the end of their time in London, about 1765. In fact, the young Mozart dedicated his first sacred composition “God Is Our Refuge” (K. 20) to the museum.

Founded on 7 June 1753 the British Museum officially opened its doors on 15 January 1759 after finding a suitable building. One of the initial buildings considered to house the collection was Buckingham House, which was later rebuilt as Buckingham Palace. Where would King Charles live now if things had been different. Alas, we may never know.

Initially, the collection comprised of objects bequeathed to the nation by Sir Hans Sloane after his death. His collection was made of manuscripts, a vast number of natural history specimens, and a “cabinet of curiosities” whose massive and varied collections defied categorical boundaries. The collection soon, and often, expanded. It eventually spun off two separate and related museums, the Natural History Museum – dedicated to collections of environmental artifacts – and the British Library – which houses books, manuscripts, and other written materials. Two interesting pieces in the early collection were the Lindisfarne Gospels and the sole surviving manuscript of Beowulf, both of which are now in the British Library.

One of the centerpieces of the museum since its acquisition are the so-called “Elgin” or Parthenon Marbles. Initially built as part of the Parthenon of Athens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the marble sculptures were removed from Athens from 1801 to 1812. The largest portion was removed in 1806 by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, who had been ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803, which at the time controlled Athens. Elgin has said he removed the sculptures with permission of the Ottoman officials, but that claim has been disputed. Ever since 1835, when Greece gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire, it has been demanding their return. So far, despite UNESCO concluding in 2021 that the British government had an obligation to return the marbles, they remain in London.

More pieces in the museum are disputed by the countries and peoples from which they were acquired – some say looted. Some of these include Ethiopia, which has claimed the Tabots, a set of Pre-Axumite civilization coins; Nigeria, which claimed the Benin Bronzes; Egypt wants the Rosetta Stone back; and China has demanded the return of scrolls, manuscripts, paintings, scriptures, and relics found in the Mogao Caves of the Dunhuang region of China. The museum even has pieces of Nazi plunder which, let’s be honest, is not a good look. The museum website does list these Nazi-plundered works and investigates claims for restitution, but that’s the least it could do.

Complicating the matters is the 1963 British Museum Act, which actually forbids the British Museum from disposing of its holdings, except in a small number of special circumstances. In 2002, the Director of the British Museum, Dr Robert Anderson, stated that the "restitutionist premise, that whatever was made in a country must return to an original geographical site, would empty both the British Museum and the other great museums of the world." People (and places) in power really object to giving it up willingly. It’s a controversy that remains a heated topic of debate.

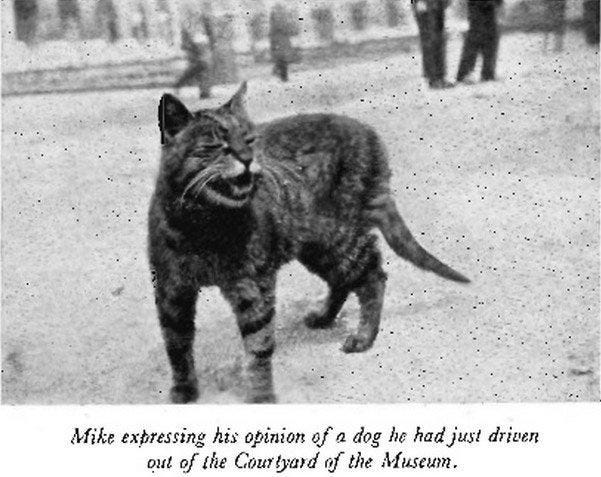

Hey, at least they once had a famous guard cat. Between 1909 and 1929 the Museum gate was guarded by a cat named Mike. When he died his obituary even appeared in the Evening Standard and Time magazine. His tombstone was erected near the Great Russell Street entrance.