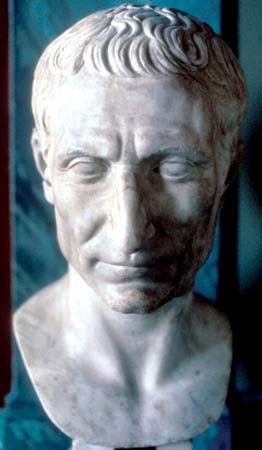

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. Actually, I come to do neither. Caesar is long dead, so there’s nothing for me to bury; and he was a bastard (not in the old-fashioned born out of wedlock sense, but in the more common phrasing that he was a jerk), so there’s not much to praise. But, hey, Brutus and Mark Antony are honorable men, I’ll let them do the burying and praising. I’m here to tell you about the Ides of March and the assassination that happened on this day in 44 BCE.

That’s 15 March in case you don’t understand the Roman calendar. It was a lunar-based calendar theoretically established by the legendary founder and first king of Rome, Romulus. Unlike our modern calendar that numbers every day in the month, the Roman calendar only had three fixed days, and even those weren’t consistent. The year started on March first, and each of the ten months had 30 or 31 days. Romans counted back from the fixed points which were mean to represent different phases of the moon – the new moon of the Kalends (1st of the following month), the full moon of the Ides, (usually the 13th day of the month except for March, May, July, and October when it was the 15th), and the quarter moon of the Nones (8 days before the Ides, which meant either the 5th or 7th of day of the month). Since all of that doesn’t actually equal a full solar cycle (one trip around the sun), the Romans threw in a bunch of market days, festivals, and religious days that weren’t part of any month to make up the extra time. If that sounds confusing, you’re not alone.

Julius Caesar found it troublesome, too, so he revised the Roman calendar to create the Julian Calendar. I mean, not him personally, obviously. He was too busy killing Gauls, his fellow Romans, and others who got in the way of his political ambitions. In 46 BCE, after Julius defeated his rivals in a bloody civil war to become dictator for life, he ordered a reformation of the calendar. Mainly this involved inserting ten additional days throughout the calendar as well as a leap day every four years to more closely align the Roman calendar with the solar year. After Julius was assassinated, his loyal friend and general Mark Antony had Caesar’s birth month, previously called Quintilis, renamed Iulius (remember, there’s no J in the Roman alphabet), which became July. Later, Julius’ nephew and successor, Octavian, aka Augustus, also eventually had a month named after him, August.

This new-and-improved (oxymoronic term, anyone?) Julian Calendar, with only slight modifications – the most importants being a fixed 7-day week with Sunday a holiday and a fixed number system – became the standard throughout Europe for centuries. It was only replaced by the Gregorian Calendar – the one most of the world uses today – in the 16th century.

One important note about the Gregorian Calendar. Being named after the Pope who commissioned it – Pope Gregory XIII, who served as Pope from 13 May 1572 to 10 April 1585 – there are obviously a lot of Christian-centric terms in the calendar itself. Two notable phrases used are BC and AD, which are “Before Christ” and “Anno Domini,” translated from Latin as “Year of Our Lord.” In a bid for inclusivity, I am, like many historians of the modern era, substituting BCE, or Before Common Era, and CE, Common Era.

The occasional word or phrase from old calendars still filters through to the modern world. One of those is Ides, which was the full moon back in March of 44 BCE. It just happened to be the day that Julius Caesar was assassinated. Remember to beware.