The Iberian peninsula, comprising Spain and Portugal today, has a long and fascinating history. It was part of the ancient pre-Celtic world – like those who built Stonehenge – has ties to the ancient Phoenecian and Greek colonies along the Mediterranean coast, was conquered by the Roman Empire, home to “barbarian” clans like the Vandals and Visigoths, and overrun again the massive Islamic expansion of the 7th and 8th centuries, only to eventually be united by Catholic rulers in the middle ages. There are lots of people and cultures in that small area!

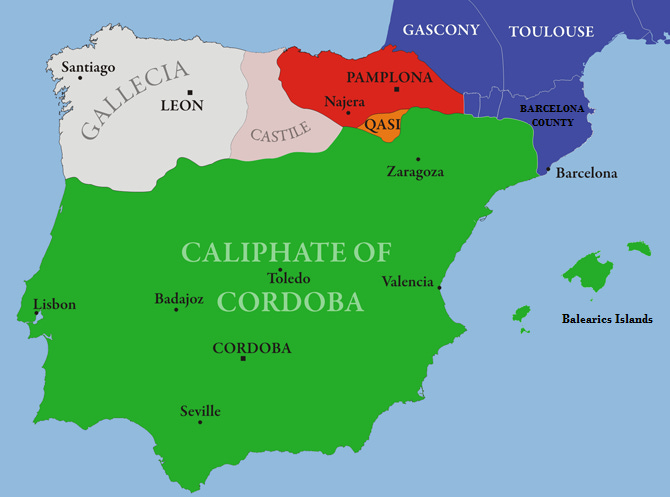

The Muslim influence in Iberia, called Al-Andalus in Arabic – from which we derive Andalusia – was perhaps greatest during the Caliphate of Córdoba, founded 16 January 929 by Abd ar-Rahman III (or, to give his full name, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil). You can see why it was shortened.

The caliphate rose from the Emirate of Córdoba, which was first established as an independent kingdom by Abd ar-Rahman I in 756. It was part of the Umayyad dynasty, which had been overthrown in much of the rest of the Islamic world by the Abbasid Caliphate in 750. There are religious and political undertones to the differences between “emirate” and “caliphate” dating back to the founding of Islam. “Emir” roughly translates to prince, while “caliph” – the ruler of a caliphate – translates to king or emperor. Abd ar-Rahman III had been Emir of Córdoba since 912 before declaring himself Caliph in 929, thus founding the caliphate. Charlemagne had done something similar centuries before – he was a ruler of the Frankish Kingdoms before declaring himself Emperor (and “founding” the Holy Roman Empire. More on all of that in future On This Dates).

The caliphate enjoyed great prosperity and cultural relevance. It grew beyond the borders of the peninsula into North Africa and Mediterranean islands. It maintained friendly relations with the Christian kingdoms to the north and throughout Europe, including the Franks, the Germans, and the Byzantines. It was a cultural haven with massive libraries of translations of ancient texts into Arabic, Latin and Hebrew. Under the caliphate there were advancements in science, arts, architecture, history, geography, and philosophy.

Religious tolerance was a mainstay. While ethnic Arabs were at the top of the social hierarchy, Muslims in general had higher social standing than Jews, who in turn were higher than Christians. Any non-Muslims were considered protected peoples (dhimmis), allowed to practice their religion and customs, as long as they paid jizya, or tax.

But the good times were not to last. Advisors, military leaders, and other Muslim powers all jockeyed for power. A civil war began in 1009, known as the Fitna of al-Andalus. The conflict would eventually divide the caliphate into a number of taifas, or independent kingdoms, in 1031. Those taifas, cut off from the strong leadership of an emir or caliph, eventually fell to the northern Christian powers, in a period known as the Reconquista. By 1246 Christian leaders had conquered everything except for the Emirate of Granada. That, as discussed previously, fell in 1492.

For a few centuries, Muslim al-Andalus was a paragon of art, science, culture, and religious tolerance. It’s important to remember those good times.