After Granada surrendered to the Spanish Catholic monarchs in January 1492, the “Reconquista” was over (the idea of the “reconquest of Spain” is mostly a 19th and 20th century invention aimed at creating a myth of Spanish nationalism dating back centuries, but that’s not the point). With Spain “safely” back in Christian hands, Ferdinand and Isabella could turn their attention to other militaristic and economic opportunities (paying for war costs a lot of money). When Christopher Columbus presented them the possibility of tapping into the trading riches of “the East,” they took the shot. This resulted in the Capitulations of Santa Fe, which were signed on this date, 17 April 1492.

The overland trade route from Europe to Asia, the so-called “Silk Road,” had been in existence for more than 1500 years by the time of the Capitulations. It ran from China in the east, through the “-stans” of Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, etc.), India, Iran (ancient Persia), Iraq (Mesopotamia), the Holy Lands (Syria, Lebanon), and into Turkey (the Byzantine Empire). There were some sea lanes throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and India, as well, though for Europeans those were harder to reach initially, since the Suez Canal that provided access from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea was not built until centuries later. With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Muslims in 1453, one of the main Christian European demarcation points was no longer accessible.

Despite the myth, most of the world did believe the Earth was round, though they didn’t know the exact size. Columbus had been trying to get European leaders to fund his expedition for decades. He’d contacted the King of Portugal in 1484, Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486, and even King Henry VII of England in 1491, but all initially rejected him, believing his calculations about sailing West to reach the East were highly improbable. Finally, the Spanish crown agreed to fund the expedition, after much discussion with their advisors, understanding that the downside would be minimal (a few ships, crew, provisions, etc.), but the upside could be worth a lot more.

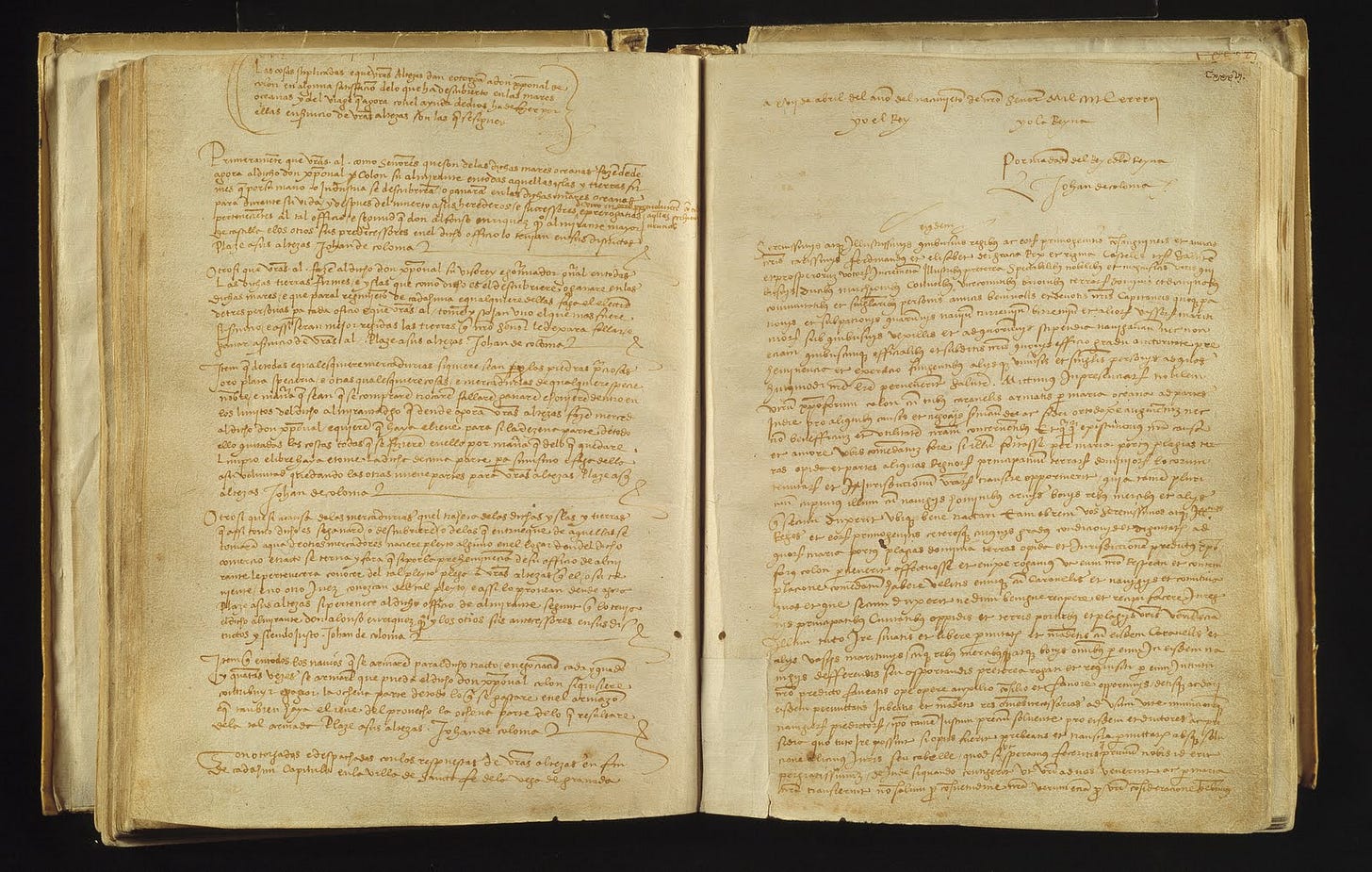

The Capitulations were signed in the town of Santa Fe in the province of Granada, and laid out the conditions of Columbus’ voyage and remuneration. The original version does not survive; the earliest version was issued by the Crown in Barcelona in 1493. If he were successful, they granted him the titles of “Admiral of the Ocean Sea” and appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands he might claim for Spain. He would also receive ten percent of all the treasure from the lands he could secure, and have the option to purchase and interest (and therefore profits) in any commercial venture in the new lands.

Columbus’ good fortune (pun fully intended) came to a halt when he was arrested and sent back to Spain in chains after his third voyage in 1500. Other Spaniards in the New World were jealous of Columbus’ new wealth and power, and he was also reportedly a poor governor because he mistreated the native population, often brutally (though the Spanish crown didn’t really care about mistreated “heathens”). Columbus and his heirs sued the monarchs in a series of lawsuits known as the “Pleitos Colombinos.” Between 1508 and 1536 a series of decisions affirmed and rebuked Columbus’ titles and wealth. Eventually, in 1536, his heirs were awarded lordship over land in Jamaica and Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the title of Admiral, and a small annual stipend. Columbus (dead since 1506) and his heirs were stripped of the titles of Viceroy and Governor, as well as the perpetual ten percent of wealth of all treasure. Minor lawsuits continued until the middle of the 18th century.

In 2009 the Capitulations of Santa Fe became part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.