Flying is the safest form of transportation. At least nowadays (unless you fly on a Boeing plane, in which case, don’t). Back in the 1920s and 1930s, it was still a burgeoning field, full of daring trials and perils (and this is before Boeing!). In the early age of aviation, flying was dangerous yet exciting, full of thrills and famous pilots who gained international renown with their daring feats. Who hasn’t heard of Charles Lindbergh – the first man to fly nonstop from New York to Paris in his Spirit of St. Louis – or of Chuck Yaeger – the first person to break the sound barrier – or Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron,” the daring German flying ace of WWI who had over 80 confirmed aerial victories. These names are legendary. So too is Amelia Earhart, another aviation pioneer, who went missing over the Pacific Ocean on this date, 2 July 1937.

Born in Atchison, Kansas on 24 July 1897 and raised all over the midwest, Amelia didn’t start flying until the early 1920s. She trained as a nurse during WWI, and in performing her duties treating patients at a hospital in Toronto, she heard stories from military pilots that first piqued her interest in flying. During the 1918 Great Influenza (sometimes misnomered as the Spanish Flu), Amelia became infected and was hospitalized for pneumonia and sinus-related problems, which would plague her for the rest of her life. These sinus problems were related to mucus drainage via the nostrils and throat, and she sometimes wore a bandage on her cheek to cover a small drainage tube to help her breathe.

While visiting her father in California in December 1920, the two attended a small air show in Long Beach, which offered passenger flights and flying lessons. Amelia took her first flight as a passenger on 29 December 1920, a 10-minute trip which cost $10 and changed her life forever. She later said that she knew almost upon takeoff that she had to fly. Days later, in January 1921, she began her flying lessons, which cost $500 (about $7800 today). She worked many odd jobs to pay for the lessons, and on 16 May 1923, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), or World Air Sports Federation, issued Amelia her pilot’s license, only the 16th woman in the US issued one at the time. She had already set world records for female pilots, and continued to do so until her disappearance. Among them were the first woman to fly the Atlantic Ocean (as a passenger) in 1928, and multiple awards and records in 1932, including the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo, the first person to fly the Atlantic twice, the first woman to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the first woman to fly nonstop coast-to-coast across the US.

Amelia was also a founding member, and first president, of The 99s, or Ninety-Nines, the International Organization of Women Pilots which still provides training, mentorship, networking, and flight scholarships for female pilots all around the world. She was also a promoter of commercial air travel, wrote best-selling books about her flying experiences, was a member of the National Women’s Party which fought for women’s suffrage and equality, and supported the Equal Rights Amendment.

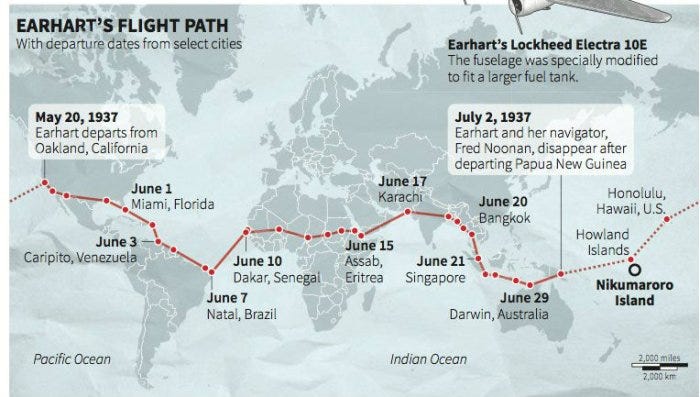

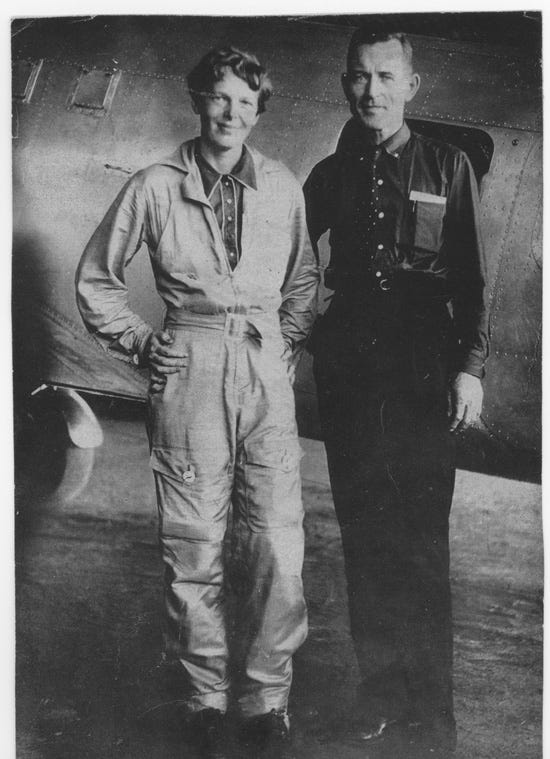

Yet it is Amelia’s death, or disappearance, which has captured the imagination of future generations. While attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world, Amelia and her navigator Fred Noonan disappeared. She and Noonan left Oakland, California on 1 June 1937, flying west to east. They made numerous stops in South America, Africa, throughout the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia, and eventually arrived at Lae, New Guinea, on 29 June 1937, their last known location.

They had flown 22,000 miles, with 7000 more to go before returning to Oakland. They departed from Lae and headed 2500 miles toward Howland Island, a small island in the central Pacific Ocean, but were never seen again. Most people assume they ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean. Amelia and Noonan were officially declared dead on 5 January 1939, eighteen months after their disappearance.

Decades later, her death remains mysterious yet her legacy is strong. Ameila was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1968 and the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1973. She’s had numerous commemorative memorials in the US named in her honor, including a stamp, an airport, a museum, a library, and multiple roads and schools, not to mention a minor planet. We may never know what actually happened, though one explorer in 2024 claims to have found the lost plane.