The history of tennis is peppered with the names of champions and personalities that even casual people would recognize. These include the inestimable Venus and Serena Williams, the classy GOAT (in my opinion) from Basel Roger Federer, the reigning Olympic men’s Gold Medal singles winner Novak Djokovic, fiery tempered John McEnroe, German sensation Steffi (or, as she prefers, Stephanie) Graf, legends like Rod Laver and Martina Navratilova, and the ever-progressive Billie Jean King. But long before the sport became a professional career for these stars, there were a bevy of amateurs who played for the love of the sport and broke a few landmarks along the way. One of those amateur tennis players who broke barriers was Althea Gibson, and she was born on this date, 25 August 1927.

Born in South Carolina to sharecropping parents, Althea Gibson and her family joined the Great Migration when they moved north to Harlem in 1930, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. There young Gibson began playing many sports including paddle tennis (almost a cross between table tennis and regular tennis), winning her first tournament at the precocious age of 12. With the help of funds from the locals in her neighborhood she was able to take formal tennis lessons beginning in 1940, and soon began winning national tournaments. She then received sponsorships and funding to attend high school in Wilmington, North Carolina before enrolling in the historically black (HBCU) Florida A&M University (FAMU) with a full athletic scholarship.

Despite her qualifications as an elite-level player, in the racially segregated makeup of America during the 1940s and 1950s, Gibson was effectively barred from playing in the premier American tournament, the United States National Championships (now known as the US Open) at Forest Hills. Technically the rules prohibited racial or ethnic discrimination, but players qualified for the Nationals by accumulating points at sanctioned tournaments, most of which were held at white-only clubs. After intense lobbying from friends and supporters, including the oldest Black sports organization in the United States, the American Tennis Association (ATA), the organization that ran Nationals allowed Gibson to compete. She became the first Black player to receive an invitation to the Nationals, where she made her Forest Hills debut a few days after her 23rd birthday in 1950. Though she lost that year, she continued to play all around the world.

Between 1956 and 1958, she packed in wins and accomplishments. During that time she appeared in an amazing 19 major Slam finals between singles, doubles, and mixed doubles, and won 11 total titles, compiling an impressive 53-9 record at the major Slams (16-1 at Wimbledon, 27-7 at the US, 6-0 at the French, and 4-1 at the Australian). When she won at Wimbledon in 1957, she became the first Black champion in the tournament's then 80-year history, and the first champion to receive the trophy personally from Queen Elizabeth II. Gibson was the first Black person to appear on the cover of Time Magazine and Sports Illustrated. In both 1957 and 1958, Gibson was named the Associated Press “Female Athlete of the Year.”

Capping off her dominance, Gibson won her last 55 matches of the 1957 season, plus her first 2 matches in 1958, meaning she won 57 matches in a row. Only four other female players have had similar streaks – Martina Navratilova, with 74, 58, and 54, Stephanie Graf with 66, and two other streaks of 45 and 46, Margaret Court, who tied Gibsob’s streak of 57, and Chris Evert once had a streak of 55 wins. On the men’s side, only Bjorn Borg ever topped 50 consecutive wins.

Though she was great on court, Gibson played in an era where only amateurs could compete in the Slams, and winners were not paid for their achievements, so her finances were in dire straits. She turned professional in 1958, though the women’s tour at the time was almost non-existent, so even that barely covered expenses. With the advent of the Open era in 1968, she attempted a tennis comeback, but she was in her 40s and could not compete with the younger players.

Tennis was not all Althea Gibson offered. She was also a gifted musician, and signed with Dot Records to record an album of popular standards. She also acted in a John Ford movie and was a sports commentator in both print and television. Most notably, Gibson was also a talented golfer, and became the first Black woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour in 1964, when she was 37. The racism and discrimination of the era continued in golf, where many hotels and country clubs refused to allow her to compete or, even if she was, she had to dress in her car because she was banned from the clubhouse. She never won a golf tournament, but was a force on and off the course.

After retiring from playing, she ran numerous clinics and outreach programs, became New Jersey's athletic commissioner – the first woman to hold a position – and ran for state Senate. Though she lost the election, she was appointed to manage the Department of Recreation in East Orange, New Jersey and to serve on the State Athletic Control Board, while also becoming supervisor of the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports.

Althea Gibson is best remembered as a tennis legend. Indeed, after she retired, it wasn’t until 1971, almost 15 years later, that another woman of color, Evonne Goolagong, won a Grand Slam championship. It took more than 40 years, in 1999, until another Black American woman, Serena Williams, won the first of her six US Opens in 1999, not long after faxing a letter and list of questions to Gibson.

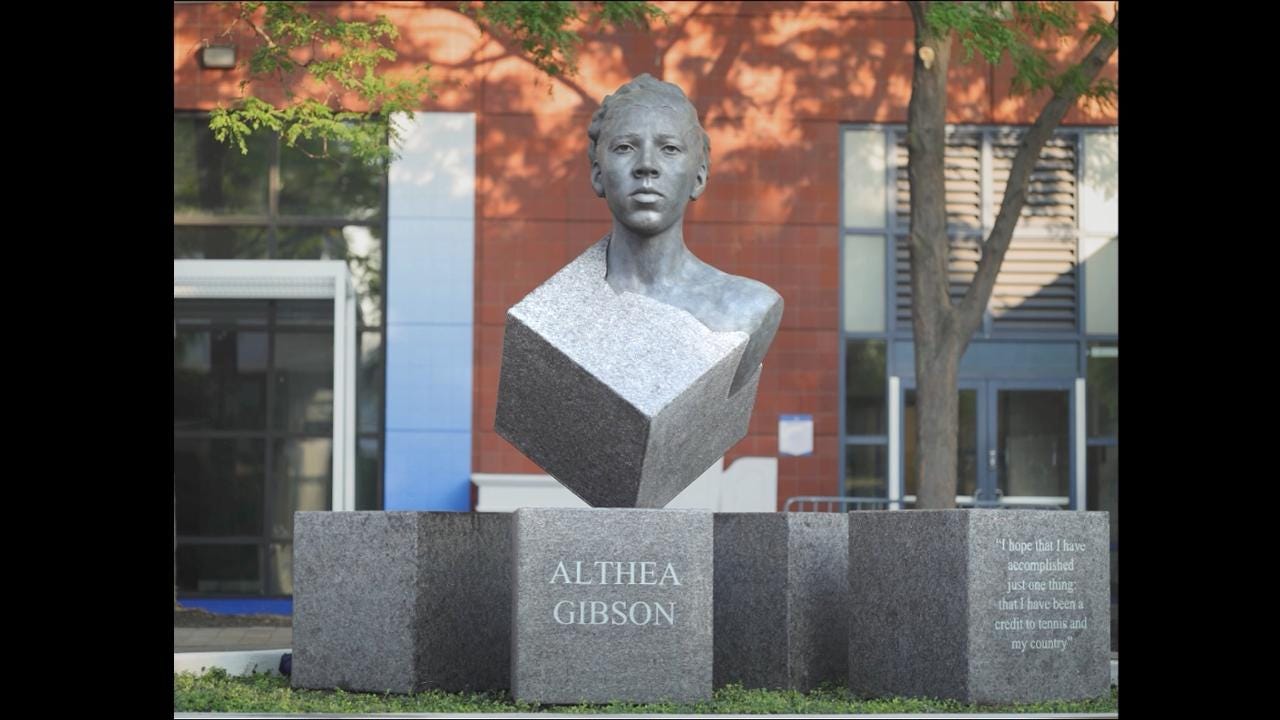

Althea Gibson’s legacy in sports has been honored by her inducted into International Women's Sports Hall of Fame, the National Lawn Tennis Hall of Fame, the International Tennis Hall of Fame, the Florida Sports Hall of Fame, the Black Athletes Hall of Fame, the Sports Hall of Fame of New Jersey, the New Jersey Hall of Fame, the International Scholar-Athlete Hall of Fame, and the National Women's Hall of Fame. At the 2007 US Open, on the 50th anniversary of her first victory there, Gibson was inducted into the US Open Court of Champions, and in 2019, a statue honoring her was erected at Flushing Meadows, now site of the tournament. She died of respiratory failure in East Orange, New Jersey on 28 September 2003.