A large group of women (and some male allies) took to the streets close to a presidential inauguration to protest something related to the government. No, it wasn’t the 2017 Women’s March (or one of the other dozens of various marches and protests to descend on Washington for political change), it was the Woman Suffrage Procession organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This Procession was one of the first large marches on Washington for political purposes and occurred on this date, 3 March 1913.

The suffragist movement – the organized effort to grant women the right to vote – began in the US almost from the beginning of the country. The original constitution of New Jersey in 1776 allowed anyone meeting certain property rights to vote, regardless of gender or race, though this was eventually modified to disallow women or people of color by 1807. By the middle of the nineteenth century individual states and territories, including Wyoming (1869) and Utah (1870), had granted women the right to vote, but there was still no national provision.

By the early twentieth century, the suffragist movement was growing and putting pressure on Washington to enact change. The day before Woodrow Wilson’s first inauguration, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns staged their procession. Wilson was an avowed anti-suffragist when he was elected in 1912, though by 1918 he made a speech before Congress advocating for women’s suffrage. The US did, of course, eventually pass the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. To get to that stage, however, the movement pressured Wilson and other politicians heavily.

Alice Paul was born into a Quaker family (they claim they’re descendents of William Penn himself) in New Jersey in 1885 and became active in the suffragist movement early in life, due to her mother’s membership in the NAWSA. Alice graduated from Swarthmore in 1905 and began working as a social worker, though soon realized she didn’t like the work and vowed to enact change in other ways. She went on to gain a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1907, and also earned a PhD from that institution in 1910. In years between obtaining her MA and doctorate, she spent years in Birmingham and London, England, where she befriended British suffragists Christabel Pankhurst, her sister Sylvia, and their mother Emmeline Pankhurst, and was arrested and jailed multiple times during suffrage demonstrations there. It was during one of these arrests that Alice met Lucy Burns.

Born to an Irish Catholic family in New York in 1879, Lucy also had extensive education in both the US and abroad, attending school at Columbia, Vassar, Yale, the University of Bonn, University of Berlin (both in Germany), and Oxford to study English and German. She was very active with the Pankhursts, and was also arrested multiple times, during which she often went on hunger strikes and was subjected to force-feeding by the authorities.

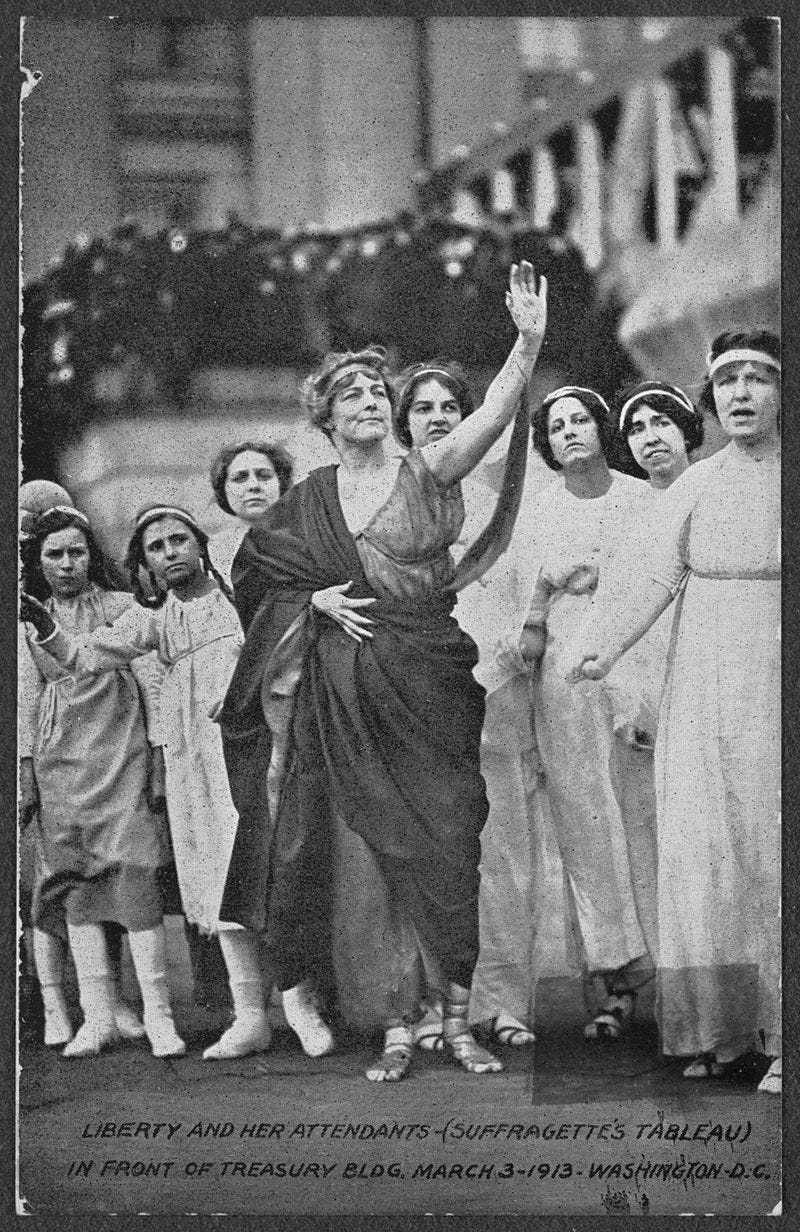

Both Alice and Lucy returned to the US in 1912 where they became leaders of the NAWSA’s Congressional Committee. This committee was aimed at putting pressure on the political party in power (the Democrats) to pass a federal suffrage amendment, rather than allowing individual states to decide the matter. One of their first acts in NAWSA was to organize the Procession, which was to have floats, bands, and various delegation groups representing women at home, in school, and the workplace, and end in a rally.

However, there were issues with the procession from the beginning, particularly due to race. The early twentieth century was the height of Jim Crow laws and racism in government – Wilson, a Southern Democrat, was overtly racist and re-segregated almost the entire executive branch, not to mention screened DW Griffith's notoriously pro-Ku Klux Klan film The Birth of a Nation in the White House in 1915. Still, Alice and Lucy supported an integrated march, even with pressure from Southern delegates saying they wouldn’t march. In the end, black women, including a group from Howard University, marched in several state delegations, while others joined in with their co-workers in professional groups.

The march was also marred by violence. A large crowd of at least 250,000 didn’t stay on the sidewalk of the route but streamed into the streets and blocked the parade. The police stationed along the procession were either unable or unwilling to control the crowds, which forced the procession to stop. The women in the march were then trapped amongst hostile, jeering men who spat on them, yelled insults, and sexually propositioned them. Some women fled, but many more locked arms and faced the taunts in their attempt to continue holding their ground. Eventually, troops from the Army arrived to clear the streets, allowing the procession to continue, ending with a rally at the Memorial Continental Hall (later part of the expanded DAR Constitution Hall) with prominent speakers, including Helen Keller.

The day after the march, newspapers around the country ran headlines about the events, which was often more prominent on the front pages than news of Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Congress soon began an investigation to determine why police crowd control was so ineffective, which kept the event in the news even longer. The Procession brought new attention and energy to the suffragist movement, which eventually pushed the 19th Amendment through Congress a few years later.

Alice continued to support women’s rights even after the Nineteenth Amendment, campaigning for the Equal Rights Amendment as well as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. She died in 1977, and was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1979 and into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2010. Lucy retreated from activism after the Nineteenth Amendment, and lived with two of her unmarried sisters in Brooklyn. She died in 1966. The Lucy Burns Institute, a nonprofit educational organization located in Madison, Wisconsin, is named after her, and in 2020, the Lucy Burns Museum opened in a former prison where Lucy was incarcerated in Lorton, Virginia.