Look, sometimes misunderstandings happen. It’s the nature of humanity and language to be interpreted differently by different people (the Austrian philosopher Wittgenstein basically argued about the meaning of words and misunderstandings in much of his later work). Just look at how many different translations of Homer’s The Odyssey there are to see how the same work can be interpreted and translated differently. Miscommunications become even more common when translating between languages. Since no two languages have the exact same context, background, or implicit understandings, translating from one to another creates problems. There are two basic thoughts about translations: the first is that written works should be translated word-for-word, sticking as closely as possible to the original material; the second is that the general meaning of the original work is more important, regardless of the specific words used. Whichever method is used, miscommunication and/or mistranslation is likely to arise. Sometimes the miscommunications are minor and can be laughed at later. Sometimes they’re massive and cause grievances for generations to come. The Treaty of Waitangi (or, in Māori, te Tiriti o Waitangi), signed on this date, 6 February 1840, is the latter sort of miscommunication.

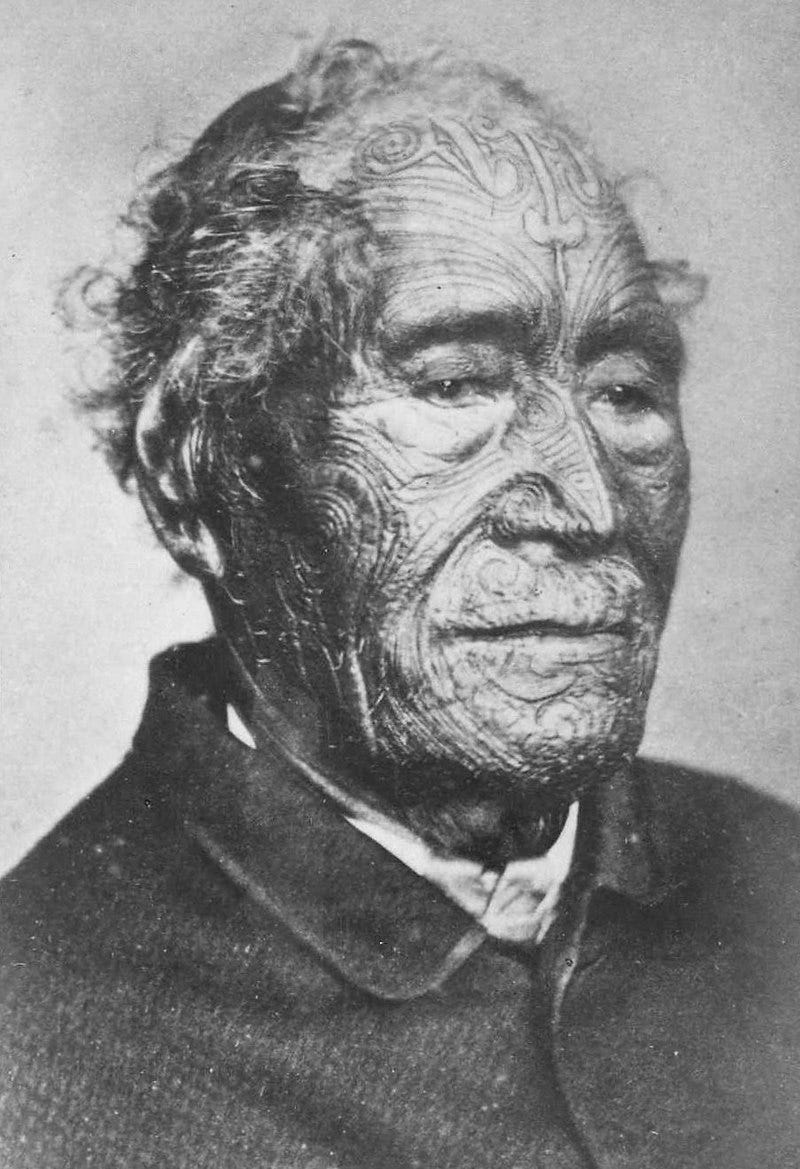

The indigenous Māori have lived on what we now call New Zealand for thousands and thousands of years. By the 1830s, a growing number of British migrants arrived and began settling. As the British Empire and colonialism went, it was relatively peaceful, all things considered. But of course it wasn’t without problems. Some settlers were unruly, there were slight disagreements between the British and Māori about territorial rights, and there was a looming threat that the French might annex New Zealand into their empire. Thinking that the Māori would be better protected under the British than the French, the British government sent diplomats to negotiate a treaty. It became the Treaty of Waitangi, or te Tiriti o Waitangi, named after the place in the Bay of Islands where the Treaty was first signed.

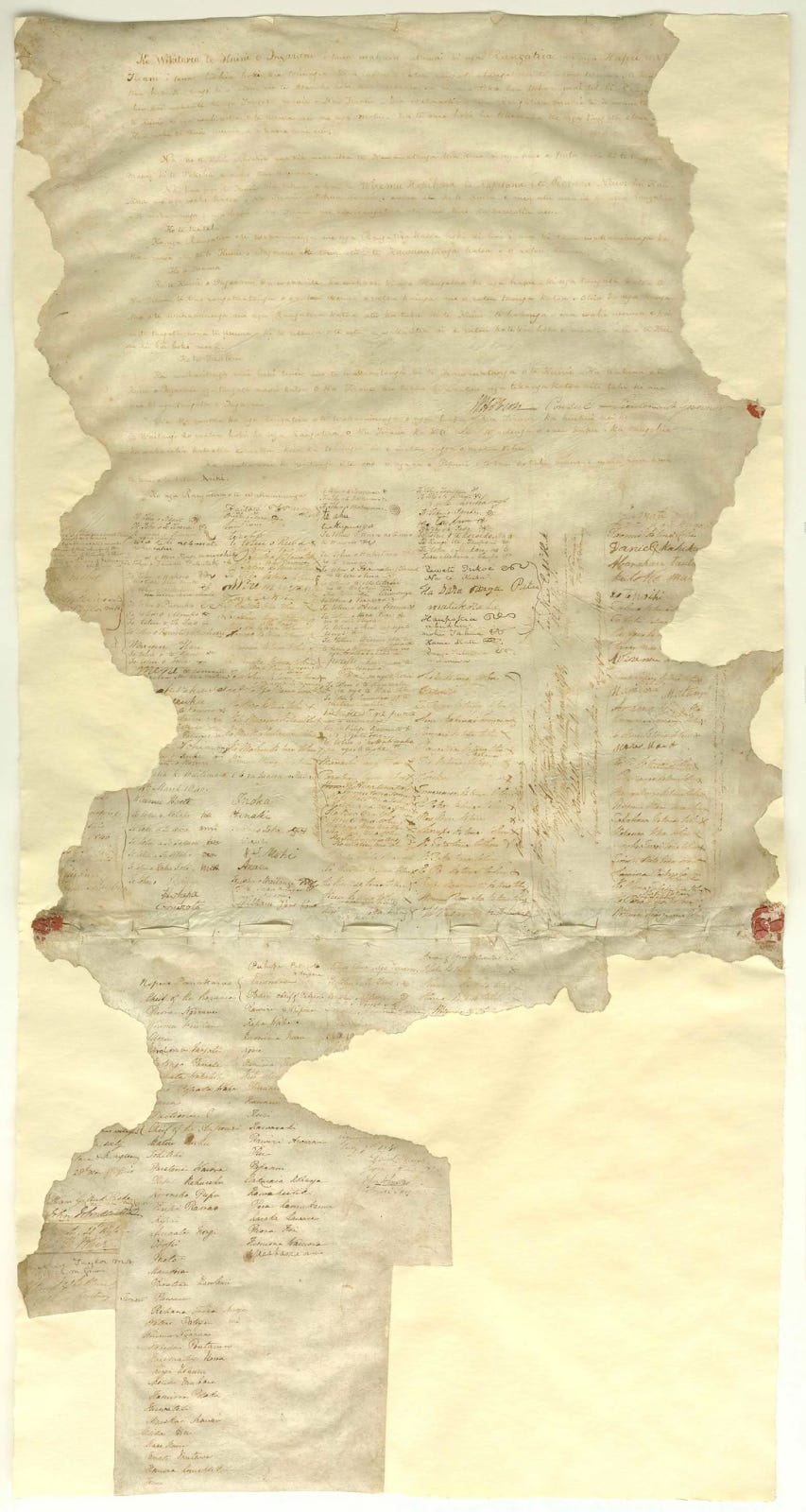

According to New Zealand’s own official government website, the treaty is considered the founding document of New Zealand. In general, it’s a broad set of principles to found a nation and build a government, set forth in three articles in both English and Māori. The English version states that 1) the Māori cede the sovereignty of New Zealand to the British; 2) the Māori give the British Crown an exclusive right to buy lands they wish to sell in return for full rights of ownership of their various possessions; and 3) the Māori are given the rights and privileges of British subjects. The Māori version is slightly different, though it was deemed to convey most of the same meaning. The biggest points of contention later became over the translation of the word “sovereignty” (“kawanatanga” in Māori, which more accurately translates as governance) and “undisturbed possession” of all properties (“tino rangatiratanga” meaning full authority) of “properties” (“taonga” meaning treasures, which can be intangible).

Shortly after the treaty was signed the British government proclaimed sovereignty over New Zealand and it became part of the colony of New South Wales (Australia) before becoming its own separate colony in 1841. As the colonial “ruler,” the British government took actions that dispossessed Māori land, waters, and other resources from their traditional Māori owners without proper consent or compensation. Some Māori aired grievances and a few early governments even attempted to address those claims, but are now considered to have been inadequate.

Though New Zealand is still a part of the British Commonwealth, the authority to govern and enforce the treaty and the claims was moved to the New Zealand Parliament. In 1975 the government commissioned the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate alleged Crown breaches of the treaty. The Tribunal has exclusive authority to determine the meaning of the treaty as translated in the English and Māori texts, with the ability to consider acts and omissions dating back to 1840. Since its establishment, the Tribunal has investigated more than 2000 claims and reached a number of major settlements.

Though the British (and later New Zealand) peoples clashed with the indigenous Māori over the meaning of the Treaty of Waitangi, te Tiriti o Waitangi, they’ve focused on redressing those issues. The treaty is considered a turning point in New Zealand history, such that the date it was signed is now a public holiday in New Zealand. Imagine what could happen if we all just talked and attempted to redress the issues of the past.