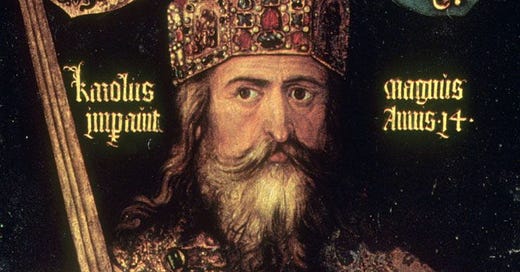

As rulers go, getting an epitaph like “the Magnificent,” “the Pious,” or “the Great” is probably a better way to be remembered than something along the lines of “the Unready” (looking at you Æthelred) or “the Terrible” (ahem, Ivan). Sometimes those epitaphs, for good or ill, become so ingrained in a person’s name that later people only know them by that moniker. Do you recognize Mary I of England? How about if I call her Bloody Mary instead? Alexander of Macedon? No, how about Alexander the Great? Any idea who Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus is? If you said Caligula, you are correct (but truthfully, how many of you knew that without looking it up? Not me. Anyway, this list of monarchs by their nickname is fascinating, as is this list of people called “the Great”). Then there’s the few lucky (ruthless?) who we might not recognize as having an epitaph because it is literally what we call them now. People like Charlemagne… or rather Charles the Great (sometimes spelled Karlus, Karlo, or Carolus Magnus), who died on this date, 28 January in 814.

From a Frankish family – originally a Germanic, “pagan,” non-Christian tribe – Charlemagne was likely born on 2 April 748, though the exact date is debated. The original Franks may have been pagan but they were unified under Clovis I in 481 and became Christian after he converted and was baptized in 508 (tribes tended to work from a “top down” approach, with the leader dictating the religious beliefs of the rest of his people). By the time Charlemagne was born the Franks were a deeply devout group. Charlemagne was particularly intent on spreading Christianity throughout his territories that covered most of Western and Northern Europe.

Charlemagne became co-King of the Franks in 768 and sole ruler in 771 upon the death of his younger brother Carloman. (Side note, does anyone else find it weird that Carolus and Carolman had basically the same name? Like little George Foreman’s of the early medieval period? Strange, right?) Anyway, Charlemagne then became King of the Lombards – a people and region in northern Italy – in 774, and Holy Roman Emperor in 800. These titles represented a massive swathe of territory under his sole control until his death in 814.

Despite having many, many children, only one legitimate son survived into adulthood to inherit Charlemagne’s unified kingdom (though many later European dynasties including the Hapsburgs and Capetians claimed they were his descendants, and most noble families in Europe somehow trace a part of their lineage back to him). His son Louis (“the Pious”) ruled the empire until 840, when it was split into three smaller kingdoms to appease his three children. These three were the kingdoms of the West, Middle, and East Francia. The West Frankish Kingdom, or West Francia, comprised what is today most of southern and western France. Middle Francia was what would eventually become most of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, parts of Switzerland, northern Italy (Lombardy), and north eastern France. East Francia became the core of the Holy Roman Empire, the territories of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

Charlemagne ruled all of that by himself (with advisors and help, obviously, but you get the point). His position as the first recognized emperor (i.e. Holy Roman Emperor) in the West since the fall of the Western Roman Empire nearly 300 years previously brought him into conflict with the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople, who styled themselves as the proper heirs of Rome as the Eastern Roman Empire (I’ve touched upon this briefly in the past, and will in future On This Dates as well).

Perhaps one of the greatest (punny!) reasons Charlemagne is thought of as “the Great” today is his avid defense and expansion of Christianity throughout Europe, which benefited him personally and professionally, in addition to the Pope as head of the Catholic Church (remember that whole thing about power struggles in the Catholic church I wrote about earlier?). Many people who lived in those territories before being conquered were not Christian, and Charlemagne was none too happy with them. He spread Christianity to them, often by force. Nowhere is this more evident than the Saxon Wars – a series of conflicts fought from 772 to 804 between Charlemagne and the pagan Saxon tribes (the Hanover area of present-day Germany). During one of the excursions in October 782 Charlemagne’s troops suffered a military defeat. Once he arrived in person he then battled the remaining forces and, in response to losing so many of his soldiers, he ordered the death of 4,500 Saxons (because nothing says Christian mercy more than wanton executions…), which became known as the Massacre of Verden. Elsewhere, Charlemagne fought constantly with the Muslims in the Emirate of Cordoba and was in regular contact with the Muslim Caliph of Baghdad over control of a few Mediterranean islands – many of which were under the Caliph’s control at the time. Perhaps somewhat surprising for the time, Charlemagne was exceptionally tolerant of Jews (unlike later Christian territories), inviting many Jews to immigrate as royal clients independent of the feudal landowners, and even employing one as his personal physician.

Another justification for “the Great” moniker stems from Charlemagne’s reforms. He standardized the monetary system throughout his territories, adopted modernized siege technologies and excellent logistics for the military, and directed a more centralized governmental structure. He also expanded access to education and promoted scholarship, encouraging monks and clerics to translate, copy, and disseminate Christian books.

Still, “the Great” does depend on which viewpoint through which you view Charlemagne. If you want to study the fall of the Saxons, for example, he’s more “Terrible.” But we in the West don’t think about him that way, incorporating “the Great'' completely into Charles’ name. Charlemagne was laid to rest in the Palatine Chapel of Aachen, which he had constructed as part of a royal palace complex as early as 792. His original tomb is lost, though the chapel remains as one of the original components of Aachen Cathedral.