As I’ve mentioned before, the Mongols ravaged across Asia and Europe from the Sea of Japan in the east to Hungary in the west, to parts of Siberia in the north, and down to the Persian Gulf in the south. It was, and still is, the largest contiguous empire in human history. Not bad for a group of peoples that began as a disparate bunch of roaming horse tribes. During their raiding, the Mongols attacked Baghdad which, after a siege that lasted almost two weeks, fell and was sacked on this date, 10 February 1258. The sack ended one of the greatest flowerings of human knowledge ever, in a period that has since been called the Islamic Golden Age.

It might be useful to have a brief history of Islam up until the period. The prophet Muhammad founded Islam in 610 in Mecca (though the Islamic calendar begins in 622). Upon his death in 632 he was succeeded by the “Rightly Guided” (to Sunni’s, at least) Caliphs known as the Rashidun Caliphate. A Caliph is supposed to be the religious and political successor to Muhammad. The Rashidun Caliphs form the heart of the split between Sunni and Shia Muslims, where they disagreed about who was the rightful successor. Those differences have crystalized and wedged the branches in a similar way to the differences between Catholics and Protestants in Christianity. After those internal divisions collapsed their power, the Umayyad Caliphate rose to power in 661 and ruled from Damascus until 750. During these early decades from Muhammad to the Umayyads, the influence of Islam exploded across the Middle East and North Africa, gaining traction everywhere from modern Pakistan in the east to the Iberian peninsula in the west – an area roughly the size of Europe. Compare this vast expansion of Islam over the course of less than 150 years with the spread of Christianity, which took close to 1000 years to reach all of Europe. The Umayyads were the last Caliphs to rule over a united Islam (and even then there were often rebellions), for when the Abbasids took power in 750 the Islamic world began splitting into rival claimants for power (such as the Emirate, and later Caliphate, in Cordoba).

Despite the turbulent history, once the Abbasids gained power they wanted their own capital to rule from and founded Baghdad in 762. It quickly became a thriving cultural and religious powerhouse, such that the Islamic Golden Age began soon after and flourished for close to 500 years. Setting exact start and end dates for such a nebulous concept as “golden age” (or for that matter a “dark age” or something similar) often raises scholarly debate, but I’ll stick with the widely cited dates of the late 8th century until the siege and sack of Baghdad in the 13th century. At the time Baghdad was the largest city in the world with a population around 1 million people. As the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, it was the center of the Islamic world.

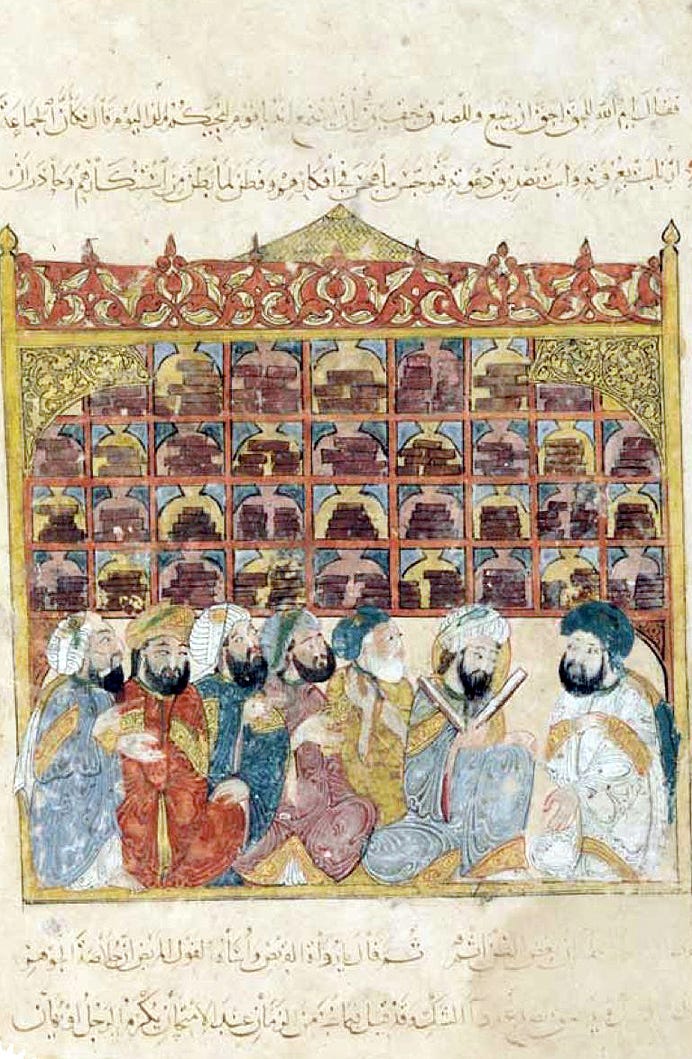

Key to this golden age was the Bayt al-Ḥikmah, sometimes called the Grand Library of Baghdad but most often referred to as the House of Wisdom. Both a public library and a center of learning, the House of Wisdom was founded somewhere around the year 770, possibly by the fifth Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, known to the West as a character in the Arabian Nights collection of stories (where we recognize heroes like Sinbad the Sailor and Aladdin. Harun al-Rashid was also the Caliph who was in contact with Charlemagne and sent elephants to his court). The House of Wisdom housed thousands of books, and saw scholars from all corners of the Muslim world flock to Baghdad.

Often the scholars worked on the Caliph’s call for translation, which saw them translating works from all languages into Arabic (though most of the translations were from Greek, Syriac, Persian, and the Indian languages). It is through these translations, which were later disseminated throughout both the Islamic diaspora world and Christian Europe that much of our modern knowledge of these ancient texts survives. In other words, there would not have been a Renaissance that harkened back to the classical Greek and Roman world without the scholars of the Islamic Golden Age preserving a copy of those texts.

Other scholars focused on original studies in fields as diverse as philosophy, mathematics, medicine, biology, engineering, astronomy, and optics. The outpouring of original scholarship was far reaching and highly influential. Many of the scholars are still known today for their originality, while others have been ignored (at least in the West). The philosopher Ibn Rushd, known to the West as Averroes, wrote commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the Western world as the “Commentator and Father of Rationalism.” The physician Ibn Sina – Latinized into Avicenna – wrote The Canon of Medicine, which was a leading medical text in the Islamic World and Europe until the 17th century. Hailed as the "father of Arab philosophy," al-Kindi was known for his translations of Greek philosophy. Amongst other notable achievements, al-Kindi also helped to introduce Indian numerals (which became known as Arabic numerals, ie 1, 2, 7, etc.) into a wider world, and develop cryptography and cryptanalysis, meaning he ensured techniques for safe, secure communications. The Persian polymath al-Khwarizmi also helped introduce Arabic numerals, and is now perhaps best known for developing algebra into a separate mathematical field. He published his landmark treatise Al-Jabr (sometimes known more formally as The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing) which got Latinized as “algebra” and has been known that way ever since. Other important scholars include al-Jahiz (translated as "Goggled-Eyed'' for his wide, staring eyes) who wrote about evolution and natural selection almost a thousand years before Darwin and al-Jazari, a physicist and engineer who is now considered the founder of robotics and modern engineering. Though now mostly known to the West for his collection of poetry called the Rubaiyat, Omar Khayyam was a noted astronomer who made such detailed and accurate calculations of the solar year that some of his designs for a calendar system are still used in Iran today.

Since women were not allowed to study or work at the House of Wisdom little was written or chronicled about them. Yet we still have fragments and brief mentions of many Muslim women who contributed to the Golden Age, even if they didn’t all live and work in Baghdad. Sutayta Al-Mahāmali was a mathematician and legal scholar who developed a formula which defined how much of an estate each heir received. A woman by the name of Al-ʻIjliyyah bint al-ʻIjliyy, often times called Mariam al-Astrulabi, was so noted for her skill in making beautiful and detailed astrolabes – an ancient device used to measure the position of the sun and stars and fix latitude – that she later had the asteroid 7060 Al-‘Ijliyah named after her. Zaynab al-Shahda was skilled in the art of calligraphy and was also well known for her knowledge of and work in fiqh (Islamic law) and hadiths (the sayings of the prophet Muhammad) that she was appointed to be the teacher of the last Abbasid Caliph, Yaqut. Fatima al-Fihriyya inherited a small fortune after the death of both her father and her husband, which she used to build the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez, Morocco, which soon expanded into the first university and institution of its kind to award degrees.

The Islamic Golden Age also saw contributions from outside of Baghdad in places like Cordoba (Spain), Cairo (Egypt), and Damascus (Syria), among others. It also included participation from non-Muslim peoples including Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, Hindus, and more. The Islamic Golden Age was a flowering of scholarship in lands controlled by Muslims but the religion itself was not necessarily the driving force. The greatest heights of the golden age had passed by the time the Mongol general Hulegu sacked the city in 1258. Baghdad never quite recovered culturally or politically, even into the modern era. Yet it was certainly golden while it lasted.

Al-Khwarizmi is the father of both algebra and algorithms. They're both named after him. I always found it odd that he was Persian, but his name was clearly Arabic. I imagine it goes back to the Arab conquest of Persia -- after the death of the Prophet -- when the Arabs attacked Persia, which already had a monotheistic religion -- Zoroastrianism.

The Arabs changed the Persian script from cuneiform to what it is now (similar to Arabic). They also changed the name of the language from 'Parsi' to 'Farsi', because the Arabic language is missing several letters -- including 'P'. They effectively tried to remove the Persian language (written and verbal) and Zoroastrianism from Persia. Many Zoroastrians fled back to India (where the Persian a.k.a. Indo-Iranian race originated) and sought asylum to practice their religion freely. These people became known as Parsee (they bear the original name of the language). (Freddie Mercury is probably the most famous Parsee.) Cuneiform would be lost to the entire world until the Brits deciphered it, centuries later, at Bisotun.

The verbal Persian/Farsi language came back -- almost through a rebirth, many years later. The Shahnameh -- The Book of Kings -- by Ferdowsi, was an epic book, written in Persian, that birthed a national movement. Persians began to speak Persian/Farsi again instead of Arabic -- though Persian/Farsi was still written in Arabic script and still is today. The verbal Persian/Farsi language came to dominate Persia once again, thanks to Ferdowsi.

Since cuneiform was lost to the Persians, so was much of Persian history. The Shahnameh was a fictional account of Persian kings. All of the characters in the book were made up, but it sparked a national interest in who the Persians were before the Arab conquest. Even the city of Persepolis (Greek for 'Persian city') had lost its original name. No one knew what it was called in Farsi. It was eventually given the name 'Takht-e-Jamshid' -- Jamshid's capital/throne. Jamshid was a fictional king/shah from the Shahnameh. Once the Brits deciphered cuneiform, the world learned its original name -- 'Parsa'.

Thanks to the Shahnameh, Persian became the primary verbal language of the country once again. And when the Ottoman Empire was split up and turned into British and French mandates -- birthing dozens of countries -- one of the first things the U.N. did was define an 'Arab nation'. An Arab nation is one where Arabic is the primary language. So, even though, Persians have historically held stronger genetic ties to Arabs than many of the modern Arab countries, Iran is not considered an Arab country. It regained its identity when the people chose their primary language as Farsi all those years ago.

I’d like to know more about al-Jahiz. Thanks for another interesting piece.