The Great City. The Queen of Cities. New Rome. Throne of the Romans. City of the Caesar. A world capital for more than 1500 years, whatever name it uses, Constantinople (now Istanbul) was a hugely influential city in Late Antiquity and in the Middle Ages. It was one of the largest cities in both urban size and population in the 12th and 13th centuries. At the time it was sacked, on this date, 12 April 1204, it had a population of anywhere from 500,000 to 1 million people (depending on the source). By comparison, London was at around 25,000 people, Paris at 100,000, the Pope in Rome ruled over about 40,000, the Italian trading powerhouse of Venice stood at roughly 65,000. The real rival powers in the area were Baghdad, which was still enjoying its Golden Age, with roughly 1 million people, and Cairo, which had grown to 250,000 people after its founding in 969 by the Fatamid Caliphate.

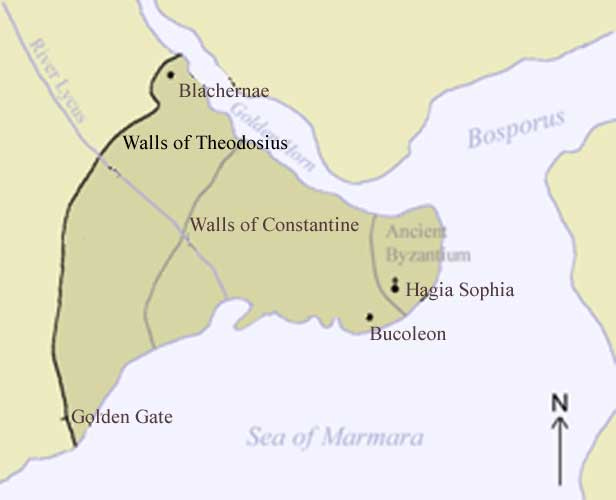

Yet it fell to European invaders in 1204, the first time the city had been conquered in its nearly 900 year history. This amazing act of defensibility was in part due to the unique position upon which it sat. Situated in a strategic location that straddled both Europe and Asia on the Bosporus strait (separating the Black Sea from the Sea of Marmara), it acted as the seaway from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and had a spacious harbor in the Golden Horne, which had its own defenses in the form of a huge chain meant to block enemy ships (you may recall a similar tactic used in Game of Thrones during the “Battle of Blackwater.” Where do you think George R R Martin got the idea from?). It also had excellent land defenses. Constantine the Great, the city’s founder in 330 (who did, yes, destroy the existing city of Byzantium and rebuilt it) initially built a single wall west of the city bounds, fortified with regular towers along the length of the wall. This was expanded by the Emperor Theodosius II (r. 402–450) who erected a set of double walls around the entirety of the city. With the triple set of walls defending against land attacks, and the numerous waterways making it practically impossible to impose an effective blockade, the Byzantines (and most potential enemies) believed the city was impregnable.

Despite the great powers of the age being the various Muslim kingdoms to the south and east, it was the lowly European warring factions that managed to breach the walls of the great city. It was a victim of the European crusader spirit (the same spirit that had created the Knights Hospitaller) and mercantile ethos that ran cities-states like Venice. The Fourth Crusade was called by Pope Innocent III, ostensibly to reclaim Jerusalem (again, after it had been lost in 1187) from Muslim forces, as well as to defeat the Ayyubid Sultanate – the Egyptian dynasty founded by Saladin, who had also recaptured Jerusalem.

Martin Luther had not yet announced his 95 Theses which sparked the Protestant Reformation, so all the Europeans were still Catholic. They believed that anyone not Catholic was heathen, even the Eastern Orthodox Byzantines (getting into the theological splits between Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestants is way, way beyond the scope of this newsletter in general, though I do touch upon it on occasion). With their abiding belief that they were the “True Christians,” the Crusade leaders contracted with Venice to transport the armies to the Holy Land.

But those leaders over-promised how many people would leave from Venice and couldn’t pay the contract. The Venetian leader, Doge Enrico Dandolo agreed to forgive the debt if the few armies that did leave from Venice would help him capture the rebellious city of Zara on the Eastern Adriatic coast (Zadar in present-day Croatia) – despite the fact that it was a Christian city – which they did in November 1202.

Later, in January 1203, the Crusader leadership entered into a separate agreement with the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos to divert a large force of the army to Constantinople to help him put his deposed father, Isaac II Angelos, back on the throne, who had agreed to financially support their invasion of Jerusalem. The Crusaders helped Alexios restore his father, and he became co-Emperor in 1204. However, he was soon deposed himself, then killed, which deprived the Crusaders of their promised money. They decided to take it from the city itself.

The Crusaders managed to seize control of some of the towers along the wall, which allowed them to punch holes in the wall for even more invaders to arrive. The small Crusader army captured the Blachernae section of the city in the northwest, using it as a base to attack the rest of the city. While defending themselves with fire, they ended up causing a huge conflagration which burned down much of the city. Now in control of the city, the Crusaders looted, pillaged, and vandalized Constantinople for three days. It was during this looting that many ancient and medieval Roman and Greek works were either seized or destroyed, including the famous bronze horses from the Hippodrome, which were sent back to adorn the façade of St Mark's Basilica in Venice.

The Byzantine nobility scattered, and ruled in exile for the next 60 years until they retook Constantinople in 1261. By that time the population had declined precipitously to around 35,000. The sacking weakened the Byzantine Empire. It allowed neighboring groups such as the Sultanate of Rum (Seljuk Turks of Central Anatolia), and later the Ottoman Turks, to gain influence, eventually resulting in the Ottoman Empire capturing Constantinople in 1453.