All good things must come to an end (all bad things too, technically, but that’s not the famous saying). Ever since its founding and dedication, Constantinople had seen the highs and lows of being the capital of a world empire, including royal weddings and triumphs, riots, sackings, and more than 1000 years of rule. Unfortunately, for the Byzantines, or the Eastern Romans as they stylized themselves, it all came to an end on this date, 29 May 1453, when Sultan Mehmed II, known later as "the Conqueror", captured Constantinople for the Ottoman Empire.

The Rise of the Ottomans

During the Middle Ages, due to various power struggles (and especially the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258), and in part because of the Crusades, much of the Sunni Muslim world had begun to flounder and break into smaller rival territories. One such was the Sultanate of Rûm, founded by Seljuk Turks in 1077. The Seljuks suffered a major defeat to the Mongols in 1243, effectively becoming their vassals who let the rule petty independent principalities, known as beyliks. One such beylik in northwestern Anatolia (Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey) was ruled by a Turkish leader Osman, who came to power in 1299.

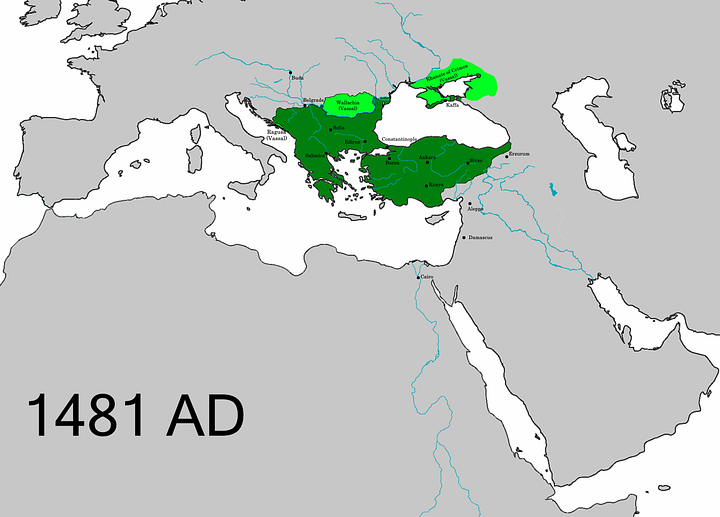

The Ottoman Turks were just one of numerous steppe people who relied on horses and raiding for their wealth and glory, much like their Mongol cousins (they all originally came from the central steppes of Asia). Having been granted the region of Bithynia, adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea near Constantinople, Osman set out to expand his territory. He soon began to extend control over Anatolia and the Balkans (modern-day Greece and the rest of the adjoining peninsula, including, but not limited to, Bulgaria, Croatia, Serbia, and Albania). Within 100 years the Ottomans, named after its founder Osman, controlled nearly all Byzantine lands except Constantinople and lands directly surrounding the city.

The city never fully recovered economically or politically after the sack of 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. The bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, which struck Europe from 1346 to 1349, further weakened the city. With almost no money to pay an army, and little to defend itself outside of its famous chain in the Golden Horn and the thick Theodosian Walls, Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire were flailing by 1453.

The Ottomans began a long siege of Constantinople that spring. Led by a young, energetic leader, Mehmed II was just 21 years old at the time. Under his command were a mixture of native Ottoman troops and recruits from outside the burgeoning empire. The total number is somewhere around 60,000 troops, including the elite Janissaries (one of the first infantry units to employ firearms) as well as Serbian calvary, Chinese engineers, about 70 cannons, as well as a fleet to blockade the city. This was compared to about 7000 total defenders for Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos in Constantinople.

Over the course of 59 days, Mehmed employed a Hungarian engineer named Orban to create the largest cannon ever produced at the time. Known as “Basilica”, the 27-foot-long cannon could hurl a 600-pound stone ball over a mile. The cannon was so large and hard to load that it could only shoot a cannonball every three hours and supposedly collapsed under its own weight and recoil after six weeks. Still, that terrifying force, combined with the other artillery and might of the Ottomans, were enough to eventually destroy the walls and allow them entry.

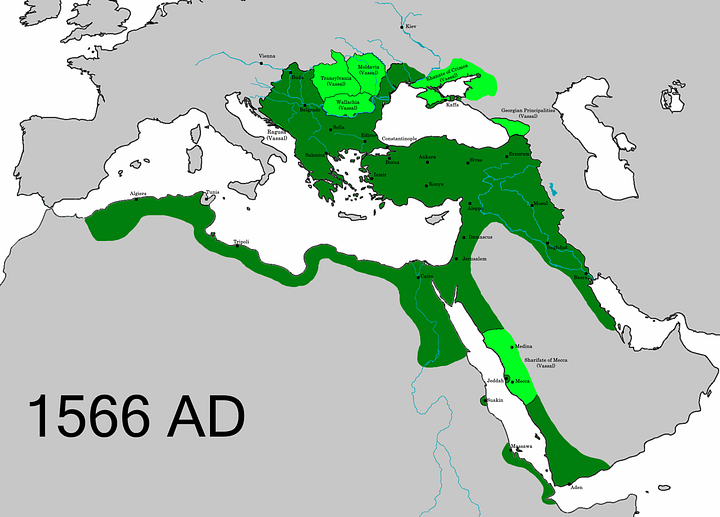

Mehmed’s troops looted the city thoroughly. When the Sultan finally entered Constantinople on 2 June, he found it largely deserted and half in ruins, with desecrated churches plundered of their treasures, shops and stores emptied of their goods, and houses no longer habitable. The destruction supposedly moved Mehmed to tears of despair. Still, Mehmed named Constantinople his new capital city, and the Ottomans ruled from there for nearly 500 years.

The conquest of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire and the entire Roman Empire, a state which had lasted nearly 1500 years. The fall of the city often delineates the end of the medieval period and the beginning of the early modern period, marked by the Renaissance in Europe, colonialism, a rapid spur of technology and science as seen in the Industrial Revolution, and more connections between global powers.